Introduction with Evidence-Based Practice

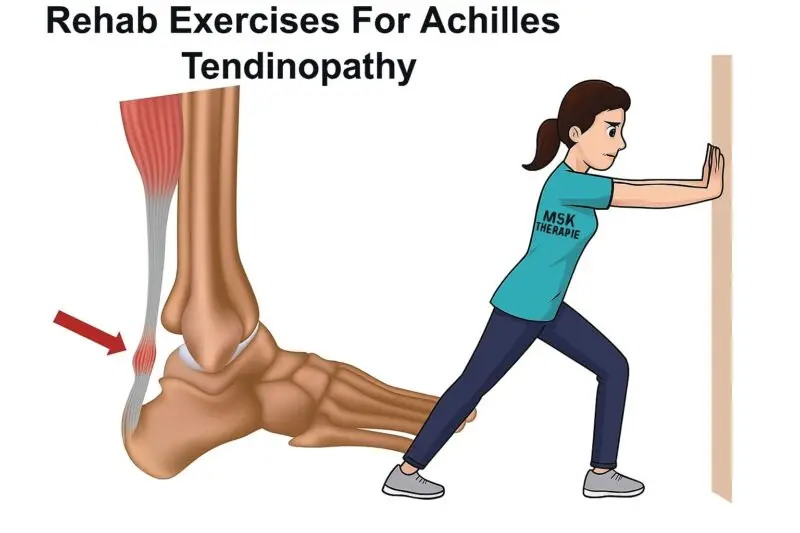

Achilles tendinopathy is one of the most common overuse injuries, particularly among runners, athletes, and individuals engaged in repetitive lower limb activity. This condition affects the Achilles tendon — the body’s largest and strongest tendon, connecting the calf muscles to the heel bone (calcaneus). Despite being a robust structure, the Achilles tendon is highly vulnerable to wear and tear and injuries because of overuse and inadequate blood flow.

Recent studies emphasize the shift from inflammation-based models (tendinitis) to a more accurate understanding of tendon degeneration (tendinopathy). According to the 2018 clinical guidelines published by the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy (JOSPT), Achilles tendinopathy is best understood as a degenerative process rather than a purely inflammatory one. Histological examinations have shown collagen disorganization, increased ground substance, and neovascularization rather than typical inflammatory cell infiltration, highlighting the importance of appropriate, evidence-based interventions like eccentric loading and activity modification over anti-inflammatory treatments.

Causes of Achilles Tendinopathy

Achilles tendinopathy arises from multiple intrinsic and extrinsic factors that contribute to tendon overload and degeneration. These can be broadly categorized as follows:

- 1. Mechanical Overload: Excessive or repetitive strain on the Achilles tendon is the most common cause. This is frequently seen in runners, dancers, and athletes who perform jumping sports. Sudden increases in activity intensity, frequency, or duration — often without adequate recovery — can overload the tendon.

- 2. Poor Biomechanics: Abnormal foot posture, such as overpronation (flattening of the arch) or leg length discrepancies, can alter the tendon loading pattern, contributing to excessive strain. Calf muscle tightness and reduced ankle dorsiflexion range of motion also place added stress on the tendon.

- 3. Footwear and Training Surfaces: Wearing unsupportive shoes or switching to minimalist footwear too quickly can increase the risk of tendinopathy. Training on hard or uneven surfaces also contributes to tendon overload.

- 4. Aging and Degeneration: Tendinopathy is more common in individuals over 35. Age-related changes include reduced collagen synthesis, decreased tendon elasticity, and diminished healing capacity, making the tendon more susceptible to microtrauma.

- 5. Systemic Conditions: Conditions such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and certain antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolones) have been associated with a higher risk of tendinopathy due to impaired tendon metabolism.

Symptoms of Achilles Tendinopathy

The symptoms of Achilles tendinopathy can vary depending on the severity and whether the mid-portion or insertion of the tendon is involved.

- Pain and stiffness around the Achilles tendon, often felt during the first steps in the morning or after periods of inactivity.

- Tenderness along the tendon, particularly 2–6 cm above the heel (mid-portion tendinopathy) or at the heel insertion (insertional tendinopathy).

- Thickening of the tendon, often accompanied by palpable nodules or swelling.

- Pain during or after activity, especially with running, jumping, or walking uphill.

- Reduced strength and function — patients may find it difficult to perform single-leg heel raises or push-off movements.

Symptoms tend to develop gradually and may persist for months if left untreated, affecting both athletic performance and daily function.

Diagnostic Tests

Accurate diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy involves a combination of clinical assessment and, when needed, imaging studies:

1. Palpation Test

- How it’s done: The clinician presses along the length of the Achilles tendon, especially 2–6 cm above the calcaneus.

- Positive sign: Localized tenderness, thickening, or nodules suggest mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy.

- Purpose: Assesses pain, swelling, and tissue texture.

2. Royal London Hospital Test

- How it’s done:

- The patient lies prone on the couch with the foot hanging over the edge of the bed.The clinician palpates the most tender point of the Achilles tendon.

- The clinician then asks the patient to dorsiflex the ankle.

- Positive sign: Reduced or absent tenderness in dorsiflexion compared to plantarflexion.

- Purpose: Differentiates Achilles tendinopathy from other causes of heel pain.

3. Arc Test

- How it’s done:

- The patient lies prone with the ankle relaxed.

- clinician then palpates a palpable swelling or thickening in the tendon.

- The ankle is then actively or passively moved into dorsiflexion and plantarflexion.

- Positive sign: The swelling moves with ankle motion → consistent with Achilles tendinopathy (as opposed to paratenonitis, where the swelling stays in place).

- Purpose: Differentiates mid-portion tendinopathy from peritendinous issues.

4. Single-Leg Heel Raise Test

- How it’s done: The patient performs repeated heel raises on one leg.

- Positive sign: Pain, reduced repetitions, poor endurance, or altered movement pattern (e.g., turning the heel outward).

- Purpose: Assesses tendon function, strength, and pain under load.

5. Hop Test

- How it’s done: The patient performs single-leg hopping in place.

- Positive sign: Pain in the Achilles tendon during hopping.

- Purpose: Detects pain under high-load, plyometric stress, often used in athletes.

6. Thompson Test (Used to rule out Achilles rupture, not tendinopathy specifically)

- How it’s done: With the patient lying prone, the calf is squeezed.

- Positive sign: Absence of plantarflexion indicates a complete rupture.

- Purpose: Rules out tendon rupture rather than confirming tendinopathy

Rehabilitation and Treatment

The management of Achilles tendinopathy is largely conservative, focusing on rehabilitation, biomechanical correction, and patient education. Based on current best evidence, the following interventions are most effective:

1. Load Management

One of the key principles in treating tendinopathy is relative rest, not complete inactivity. Patients are advised to:

- Reduce aggravating activities such as running or jumping

- Switch to low-impact activities (e.g., swimming, cycling)

- Gradually reintroduce the load as pain decreases

2. Manual Therapy and Stretching

Soft tissue mobilization, joint mobilizations (especially of the ankle), and stretching of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles can reduce biomechanical stress.

3 Orthotics and Footwear Adjustments

Custom orthotics or heel lifts may reduce tendon strain in the short term. Ensuring supportive footwear is essential for long-term tendon health.

5. Shockwave Therapy

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) has shown effectiveness in chronic tendinopathy cases. It facilitates tissue regeneration and reduces pain.

REHABILITATION PHASES:

Phase 1: Pain Management & Load Reduction (1–2 weeks)

Goals:

- Reduce pain and inflammation

- Avoid aggravating activities

Strategies:

- Ice: 15–20 mins, 2–3x/day

- Heel lifts (to reduce tendon strain temporarily)

- NSAIDs (if recommended by a doctor)

- Avoid running, jumping, or stair climbing

Exercise:

- Isometric calf contractions

- Lean against the wall, push into the ground with the forefoot without heel lift.

- Hold 30–45 seconds x 5 reps, 2x/day

Phase 2: Strengthening Phase (2–6 weeks)

Seated Calf Raise (Eccentric & Concentric Focus)

Setup:

- Sit upright on a bench or with your knees bent at roughly 90 degrees.

- Place your feet flat on the ground, about hip-width apart.

- You can place a dumbbell, barbell, or weight plate across your knees for resistance. (Use a towel for cushioning if needed.)

- Slowly lift your heels off the ground over 2–3 seconds, raising them as high as possible.

- Squeeze your calves for a few seconds and then lower your heels back down slowly over 3–5 seconds, resisting gravity as you descend.

- Allow your heels to gently touch the ground before starting the next rep.

2. Slow Concentric and Eccentric Calf Raises

How to do it:

- Stand with the balls of your feet on the edge of a step while your heels hang off the edge.

- Rise up slowly onto your toes over 3–4 seconds (concentric phase).

- Pause briefly at the top, squeezing your calves.

- Lower your heels back down just as slowly over 3–4 seconds (eccentric phase).

- Repeat for 10–15 reps.

3. Isometric Calf Hold

How to do it:

- Stand tall with your feet hip-width apart.

- Raise up onto your tiptoes and hold the top position.

- Squeeze your calves tightly and maintain the hold for 20–45 seconds.

- Slowly lower your heels back down.

- Rest briefly and repeat 2–3 times.

Tip: Engage your core and glutes to help with balance during the hold.

4. Eccentric Heel Drop

How to do it:

- Stand on the edge of a step with your heels hanging off.

- Rise up using both feet until you’re on your tiptoes.

- Shift your weight to one foot, then slowly lower that heel down over 3–5 seconds.

- Return to the top with both feet and repeat on the same leg or alternate.

- Do 10–12 reps per side.

Tip: This exercise targets the muscle-lengthening (eccentric) phase to help with strength and injury prevention—go slow!

5. Weighted Eccentric Drops

How to do it:

- Hold a dumbbell or wear a weighted vest for added resistance.

- Position yourself on the edge of a step with your heels extending past the edge

- Push up onto your toes using both legs.

- Shift your weight to one foot and slowly lower down under control.

- Use both feet to come back up to the starting position.

- Perform 8–10 reps per leg.

Prognosis and Return to Activity

With appropriate treatment, most patients recover within 3–6 months. However, complete recovery may take up to a year, especially for chronic cases. Return-to-sport decisions should be based on:

- Pain-free function

- Restoration of strength and endurance

- Resolution of tendon tenderness

Preventive strategies — including proper warm-up, gradual progression of training, and regular strength exercises — are vital to avoid recurrence.

Conclusion

Achilles tendinopathy is a challenging but manageable condition rooted more in tendon degeneration than inflammation. A careful, evidence-based approach — involving mechanical load management, eccentric exercise, and individualized rehabilitation — forms the cornerstone of effective treatment. Early intervention, patient adherence, and biomechanical correction offer the best chance for a full recovery and safe return to activity.

Much appreciated, too informative and easy to read and gain deep insight about the condition and disease. Highly recommended MSK therapie.

thank you for your appriciation

ojtzqhspoigvedfdoqryjixmhnrwls